wine can take you outside your life

finding love for strangers, and if heaven is a place on earth

Since the last dispatch from Chile, friend of the newsletter Lizzy and I were punished for our wonderful meals with a bout of food poisoning, but we have recovered and remain undeterred. Forgive today’s newsletter, it’s more melodramatic than the usual. I’m feeling particularly vulnerable and tired and touched by the world.

It’s Sunday night in Valparaiso. I’m staring at container ships floating far out in the bay and colorful, faded iron rooftops below and seagulls fighting high over the sunset and the smog. I’m trying to block out a grating, distant sound so amplified that it echoes over the entire city, perhaps someone preaching, perhaps someone just enjoying the power of their voice blanketing the hills and the houses.

I’m both worn out by and in love with this place — a city of contradictions, of grit and punk and graffiti and yet also of rainbow art and quiet cobbled mazes high in the hills — but I can’t really process it. I can’t seem to leave behind the powerful memory of the 24 hours between Wednesday and Thursday afternoon.

On Wednesday, Lizzy and I left Santiago in a rental car. We were headed less than two hours south, to the Chilean countryside where some of the most famous wines in South America are produced. We knew theoretically that it would be beautiful, though it was hard to imagine from the hour-long slog through creeping, 18-wheeler traffic that took us out of the city. “Highways are the same in every country” was the most brilliant conclusion either of us could reach.

The first sign that the day was about to change was lunch. We ate a restaurant literally on the side of the highway, yet it might have been the nicest meal we’d had yet — salmon and rice and spinach and salad, all very simply made. Our first bite of the tomatoes was so intense that it was actually surprising.

The drive from lunch to Viña Tipaume, the vineyard where we spent the evening, took about twenty minutes. And in twenty minutes we went from highway to the kind of lush, verdant countryside I’ve only ever seen in romantic movies from the ‘90s. The kind of place that looks and feels like of course it would produce some of the world’s best wines.

We drove down miles of tiny winding roads, where farms stretched on every side and people slowed in their cars to wave. Tipaume itself appeared suddenly, fields of grapes seeming to reach endlessly behind the gate. And behind the vines sat the long, low home that winemakers Valentina and Yves had built for themselves. Despite the Andes lurking on every side, the land and the grapes and the sky were somehow capacious.

In 1996, Yves and Valentina bought this parcel of land in the Cachapoal Valley and planted about 15 acres of wine grapes, chief among them carménère, a French colonial import that thrives in Chile. Yves, who spent his early life helping to launch grape-growing projects all over the world, believed that his grapes could thrive through a method known as “dry farming,” where the plant spreads roots deep into the soil and depends upon moisture retained there from the winter, rather than on traditional irrigation during the summer growing season.

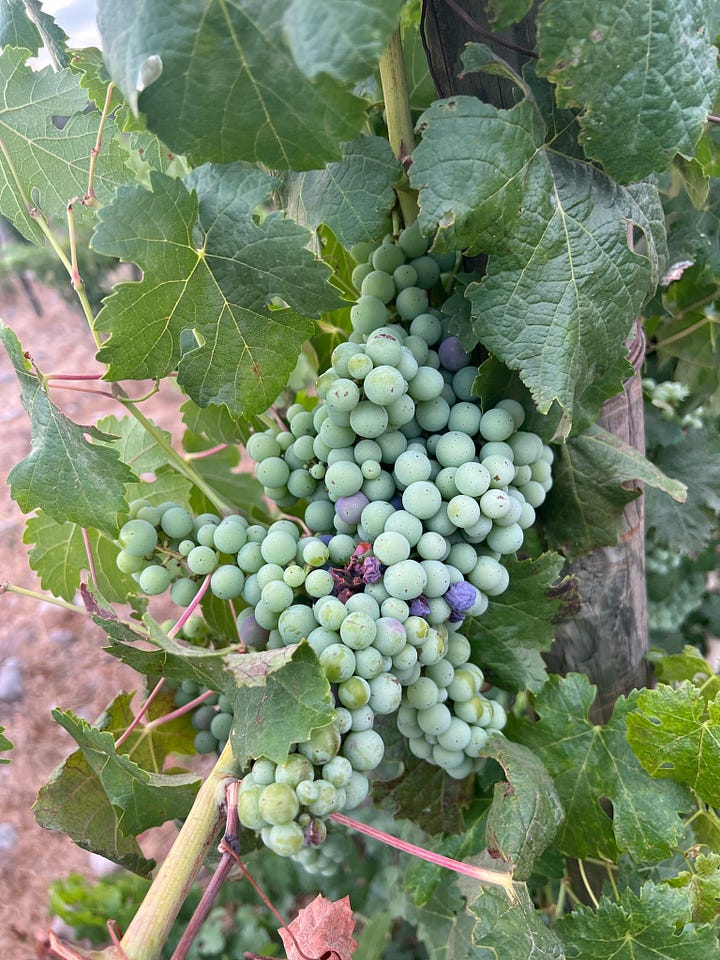

Standing among his fields, Yves plucked at the leaves as he explained this to us, pointing to the acres of green as evidence that his theory had been correct. No water anywhere to be seen, yet plants that were vibrant and loaded with clusters of ripening grapes.

It’s not just the lack of irrigation that sets Tipaume apart. The farm is biodynamically certified, a controversial status created by the founder of Waldorf education, Rudolf Steiner. (I spent my first few years at a Waldorf school and grew up eating yogurt from a biodynamic farm, a story I’ll absolutely tell in a future newsletter). “Biodynamic” farming isn’t a method they teach in the world’s leading agriculture schools. It’s a bit mystical. These farms, including Tipaume, are truly low intervention. They avoid the use of even organic pesticides. They strive to create connection between the earth, the plants and the animals in ways that are more spiritual than scientific.

But so what if Yves and Valentina believe in a perhaps mystical farming practice? The grapes were thriving, the wine they produce makes people feel alive and touched by something beyond merely ethanol, and they’ve built a happy and beautiful life around their practice.

These two people couldn’t have been kinder or warmer to us, two wine-ignorant American girls who wandered into their home without any real idea of what makes a wine “good.” That evening, as we sat in the cool, tannic-smelling unfinished cellar under the house, drinking a bottle of wine aptly named “Sous la terre,” Yves didn’t want to tell us anything about what makes the wine itself special. “You tell us what you think. That’s what matters,” he kept saying.

I have no real memory of what I actually said. I remember thinking it was delicious and too easy to drink, and then I was just drunk. I remember eating more tomatoes that just exploded into the mouth, and Valentina telling us the tomatoes in Rengo were some of the best in the world. I remember standing up to hug them and feeling a deep, exhilarating head rush, followed immediately by a splitting headache that haunted me the rest of the night.

You probably can’t find any of their wines in the United States. They only make about 7,000 bottles a year. I’ve got no idea if a really serious wine person would love their wines, but they do enough business with some of the best restaurants in Chile and around the world to survive when other small winemakers are shutting their doors (at least according to Yves).

None of that is really the point. That night — and the next morning, eating figs and drinking tea for breakfast and staring out over the fields — took me outside of myself. It reminded me that someone can reach into your life and shake you and wake you up and sink into you, and you don’t have much say over who does it or when.