Happy Sunday from Bite into this. I re-watched Julie and Julia for the first time this week in many years, which inspired today’s newsletter, an ode to the Joy of Cooking. We’re finally living in the era where the Joy is unknown to the youngest people learning to cook, so today I argue in favor of its continued value. If you’d rather a recipe to inspire your cooking, check out last week’s newsletter, on strawberry shortcakes.

I know we’re living in an odd era because the problems with the internet have seeped all the way into home cooking.

A recent Google search for a spanakopita recipe yielded thirteen equal-seeming but widely-varying recipes on page one, from sources as varied as Dinner at the Zoo, the Mediterranean Dish, Delish.com, and the ubiquitous New York Times Cooking. Even I — a theoretically well-educated professional journalist — wished I could go back to high school for a course on media literacy in the face of that jumble. What is Dinner at the Zoo? Why do I live in a world where that’s a question I actually need to ask? Who can I trust? Can I trust anyone?

Barring existential crises, there are two ways this Google search would proceed for most people. Group one would select the first result — from The Mediterranean Dish — replete with the usual litany of text and ads and instructions at the bottom. Whether the recipe would result in a delightfully flaky, crunchy, cheesy, luscious spinach pie at the end is a bit like a game of roulette. Group two would opt for the New York Times Cooking, leaning on brand recognition to ease the decision fatigue prompted by the bewildering array of options. Whether this version would turn out delicious is a bit like a game of roulette with a badly weighted ball; a higher probability of success, given the real care the New York Times Cooking staff puts into their recipes, but still a game of chance.

Irritated and stymied, I went to my kitchen to consider giving up on the spanakopita craving that had been haunting me. And there, of course, sat secret option number three, a big red and white textbook that stands out even among my inappropriately-large collection of cookbooks.

The first edition of the Joy of Cooking was self-published in 1931 in St. Louis, Missouri by a widow with a reputation as a poor cook. Her name was Irma Rombauer, and the path of this story is so well-trod that many of you could probably tell it from here.

But for those of you don’t know the tale of the beloved Irma and her descendants, let me enjoy recounting the lore. (Pausing for a shoutout here to the professor who introduced me to food writing. CDBL, this one’s for you). Rombauer’s collection, after some initial self-publishing success, was formally printed by the Bobbs-Merrill Company in 1936, becoming the first popular cookbook to teach home cooks — many without servant help for the first time — how to fend for themselves.

The first recipes were gathered from a collection of friends and family who were better cooks than Rombauer. And unlike her friends, the woman who birthed the best-selling American cookbook of all time could write. Here are the first few lines from my 1953 edition, which she wrote with help from her daughter, Marion Rombauer Becker. “The chief virtue of cocktails is their informal quality. They loosen tongues and unbutton the reserves of the socially diffident. Serve them by all means, preferably in the living room, and the sooner the better.”

This lady was funny.

And the women — it was almost entirely women cooking at this time — would die for her, shelling out so much cash that soon there was a 1943 edition, and then there was the 1953 edition in my possession, and then editions five, six, seven, eight, and finally nine (in 2019). Somewhere along the way, perhaps by 1953, I feel safe in my assumption that the Joy of Cooking outpaced the Bible for American household ubiquity.

We have thankfully escaped the strictures of those eras, but the Joy of Cooking has survived even when the expectations of domestic bondage have not. It’s been a tumultuous time for the text. The 1962 edition, published after Rombauer’s death and without her daughter’s knowledge, was so full of errors that corrections had to be issued. The 1997 edition, an overhaul led by an exacting food editor at Scribner, wiped out Rombauer’s funny voice in favor of improved recipes that had been revised and rigorously tested by more than 100 experts, a choice reviled by many and secretly loved by others (I am one of the controversial few).

Stories about the Joy usually end on the family behind the recipes, but today I’m writing because of what’s actually inside these wonderful books. Today, the Joy of Cooking isn’t a survival guide for the torture of a mid-century kitchen. It’s instead an antidote to the affliction of recipe over-production.

The pressures and demands of the internet have sucked even the best recipe writers into the content-creation tornado; everything it spits out must be cleverer and clickier and the latest twist on the last. Recipes cannot be copyrighted, but not one of the Alison Roman’s or Molly Baz’s or Tejal Rao’s of today want to appear to be writing the same recipe that someone else published ten or even fifty years ago. The constant production of more and new that the New York Times Cooking and random internet food blogs and Bon Appetit demand leaves us haunted by lime and orange substitutes for lemon bars and strawberry sumac cake and one-pot mushroom and leek pasta. (Not that those don’t sound delicious, but how do you choose? Why can’t it be simple?) I love all of these writers and their work, don’t get me wrong — and

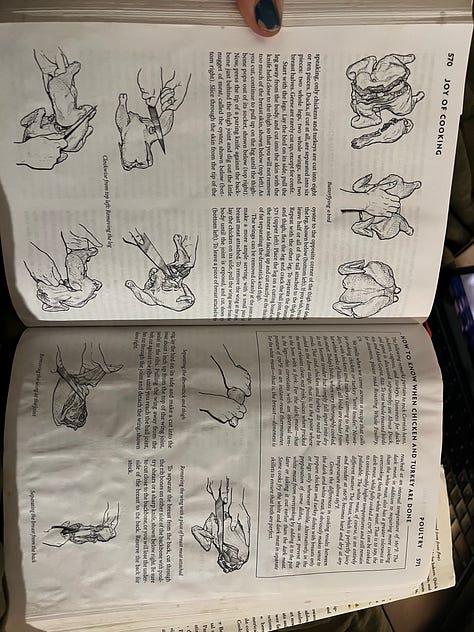

’s is a paragon of the reliable internet food blog — but I don’t need new or different or six different versions most of the time when I cook. I want reliable. I want to know that there’s one place where I can always find a useful recipe for anything I could want to make.That place is the Joy of Cooking. From filleting a fish to boiling an egg, the 1000-plus pages of this book provide explicit, accessible instructions. The index is so painstakingly organized that you could turn to C for cucumbers and find seven recipes of varying complexity, as well as a page explaining their origin and how to pick them in a store (“select firm, hard cucumbers”). If your needs are those of a twenty-two-year-old scared of the kitchen and stuck making pasta, here you can find gentle, honest guidance for simple sauces, pasta salads, and instructions on cooking a chicken breast for the first time. If you bake like I do, the sections on pies and American fruit desserts will provide more ideas for kuchens and pandowdies than I may ever have the time to attempt. The instructions for selecting, preparing, and cooking cuts of meat are so straightforward that anyone attempting them for the first time need not be intimidated. When I first lived on my own, I learned to cut a whole raw chicken into its parts from these pages, a process that baffled me before the illustrations you see below.

Almost any recipe you can think of, you will find some version in some edition of the Joy. The spanakopita, I promise from my own first-time attempt, is one fabulous hell of a home run. A very abbreviated list of other recipes I adore: chicken stock, rice vinegar cucumber salad, thai coconut rice, cheesecake cockaigne, pasta salad with feta and olives, challah bread, black-bottom cupcakes, apple pie, lentil and rice pilaf.

The text is so vast and usable that every person’s story with their Joy of Cooking will be a different one, based in their experience, their preferences, and their skill level.

For my readers with an already deep affection for this book, I’d love to hear what recipes you love and depend upon!

Some buying guidance: If you’re acquiring this book for the first time, you should buy the 1997, the 2006 75th anniversary, or the 2019 edition (this one is probably the best bet for younger cooks, and the cheapest). The true Joy aficionados will tell you to go older and more classic, but the reality is that the recipes have been tested, revised, and diversified for modern kitchens with time.

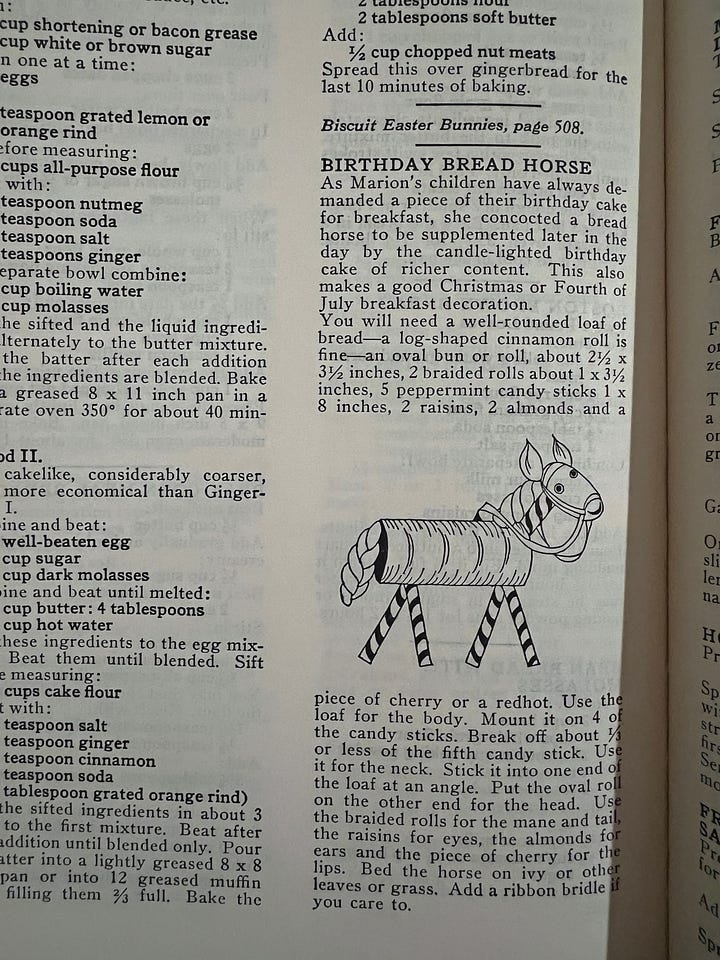

I recommend owning a second, older copy if you’re delighted by the first. These you can find in used bookstores or your parents’ or grandparents’ bookshelves or attics. The purpose of the older copy is the weirder, wilder, and often much less healthy recipes. The drinks section in the old books, for example, features the fattiest, booziest egg nog I’ve ever seen, now demanded every holiday season by my family and friends. Irma’s introduction to the egg nog, from 1953: “A rich and extravagant version that is correspondingly good. I shall not attempt to give the number of servings as I am a poor judge of thirst and capacity. An authority (Mark Twain) says, ‘too much of anything is bad, but too much whiskey is just enough.’” The recipe makes five quarts of cocktails and includes more than one dozen eggs and more than one quart of whiskey. (I’ll absolutely write a future Bite into this with my own revisions on this recipe, ideally written after immoderate consumption.)

Restaurant notes this week

an oldie but a goodie: Red Rocks, Columbia Heights. For those weird haters of Sonny’s Pizza out there, Red Rocks really is a great, reliable, wood-fired, thin-crust, neighborhood pizza and beer joint with the best outdoor vibes in the summer.

To sign us off this week, here’s strawberry shortcake testimony from my parents, who are being cute and cooking my recipes…

Wonderful! Thanks for the shout-out, Anna. You are proof of the Joy of Teaching. Erma Rombauer and Daughter are heroines of food history.

Im a secret fan of the 1997 version too. Yea, it loses the author’s original voice and writing style, but I don’t read cookbooks to be entertained. I read them yo tell me how to entertain. And the 1997 version is full of well tested professional advice