it's actually time to make apple pie

hear me out and open yourself to the world of apples in the spring

A quick apology to my wonderful subscribers. I love this newsletter with all of my heart, and I really wish I wrote it more often. I’m always struggling with a bit of guilt when I write Bite into this, torn between the thing I love most and the work that actually pays. (If we had a lot more subscribers, I would write this more often! So please share this around if you’d like that.)

If you’re curious about what I’ve been up to since I’ve been away from your inbox, here’s a link to a fun interactive piece in the Washington Post about how denim jean design is changing to become more sustainable, and here’s my recent story in Heatmap about the towns, schools, and mining sites that might replace their diesel generators with nuclear reactors so small they can fit on a truck.

When apples ripen — and eventually rot — they emit a gas called ethylene. If ethylene (a plant hormone) gets near another apple, it spurs that fruit to ripen, too, leading every apple in a container to ripen and spoil at the same rate.

Literally, one bad apple does actually spoil the whole batch.

But thanks to a couple of simple technical innovations, today farmers and grocery stores can store apples in different ways to prevent this ethylene from actually causing any ripening. The farmer I work with (shoutout 78 Acres) uses sachets that look a bit like a silica gel packet, pops them into the tubs full of apples, shuts the lid, and forgets about them. Ethylene problem vanquished, making apples the best fruit for long storage.

If you’re lucky enough to live in California or Florida or somewhere with abundant fresh produce year-round, the argument I’m about to make might be less compelling. But if you live anywhere with winter, this time of year is actually the least exciting for seasonal eating. It’s too early still for strawberries, the rhubarb is about a week away, and the greenhouse cucumbers are the first hints of better times to come. My cooking is stultified. I’m sick of butternut and autumn frost and acorn squashes, of onions and kale and maybe the occasional head of broccoli, and even of potatoes. None of these veggies are as flavorful or as perky as they were in the fall: the kale wilts in a day, the onions and potatoes are so desperate to live on that they’re sprouting despite my best attempt to store them away from sun and warmth, and the squash is developing spots of mold.

If you’ve been reading this newsletter for awhile, you know that I’m talking about farmer’s market apples. If you can get to a farmer’s market and you’re still buying apples from a grocery story, I’m taking that as a personal offense, and you can read more about that below, from the very first days of this newsletter.

the apple personality test

This is the newsletter where I rank you all based on your apple-buying personality, inspired by the fact that I realized yesterday that I know far too much about the lives of everyone buying apples from me. You all are sharing a lot with someone you don’t know. The person who told me he hopes that apples might fix his marriage could definitely use a therapist.

Unlike the rest of the winter produce, apples today are still almost exactly the same as they were in the fall. Still crunchy, juicy, crisp, and punch-you-in-the-mouth full of flavor. I’m still eating them with peanut butter for lunch and slicing them into salads at dinner.

And I’m starting to bake with them again. Apple baked goods are so quintessentially fall that I don’t usually remember them as an option at other times of year. In December, I typically get sucked up into holiday desserts (see this newsletter on gingerbread), and then in the cold dark days of my seasonal depression I’m craving the bright acidity of a lemon confection (as seen in last week’s newsletter). But for the last few weeks, as days have lengthened and my well-being has righted alongside, I’m looking to bake something different and fruity, opening the fridge, and seeing piles of apples in the drawer just waiting for a use. (Store your apples in the fridge! Apples sitting out get gross in about two days. Please stop eating mediocre apples that you’ve kept on the counter all week just because they look pretty.)

While the best application is obviously the apple pie, I’m taking a very quick detour to note that this King Arthur recipe for a “mostly apples” apple cake has become my go-to when I need a quick bake that will delight many. I’ve watched people devour half of this cake in one sitting numerous times. It’s got this lovely texture that’s slightly “financier” because of the almond flour: soft and gooey but also with the tiniest hint of a chew. You’ll need to have almond flour on hand, and I also recommend that you sub in in vanilla extract for the almond called for in the recipe (the almond is too overpowering).

But apple pie. If I still wrote poetry (and we should be thankful that brief experiment ended in high school), I would be writing an ode. Many people harbor prejudice against apple pie because the only ones they’ve ever had are sad: The diner or grocery store pies with a wet, cardboard-like crust enclosed around an apple filling that vaguely resembles sickly-sweet applesauce, only with the addition of a gooey film that coats the tongue and throat.

We have lost the art of the apple pie in 21st century America. That’s quite tragic, because there aren’t that many fabulous American dishes in the first place. Apple pies didn’t begin in the US — they came from Europe with the colonizers — but they became American because we figured out how to grow a baffling range of delicious apple varieties in the nineteenth century. With such a wide variety, a cooked apple filling enclosed in a pastry crust became much more interesting. Apples were so easy to grow, so abundant, and so cheap that many households put them into the rotation.

A truly excellent apple pie should consist of a flaky pastry, still dry on the bottom and the top, sandwiched around layers of apples that still have a little bit of bite and that carry a mix of floral, tart, sweet, and perhaps even herbal flavors. The pie shouldn’t require any more spices more than a conservative teaspoon of cinnamon or a couple of dashes of rye: if you’re loading up on the nutmeg or the allspice, you’re hiding the flavors of the apple.

The pie should gel, not leaking any serious amount of liquid, but it should not be gloopy. In contrast to other fruit pies, this texture is actually easy to achieve because apples are full of pectin, a natural thickening agent that creates the spreadable consistency in jam. Apples are also low in moisture content compared to other fruits, so you don’t need cornstarch or tapioca to thicken the filling. All you need is sugar, some lemon juice to provide the acid, salt for flavor, and a few tablespoons of flour to ensure there’s no leftover liquid. If the pie cooks for long enough in the oven, and if the crust has been vented properly, most of the water will evaporate and the filling will thicken without becoming gloopy. If you’re using quality baking apples with some structural integrity (I like Stayman, Granny Smith, Pink Lady, Crimson Crisp, Mutsu, or even Honeycrisp), the long cooking time shouldn’t disintegrate the slices. You should mix in some apples for flavor that are less tough (think Evercrisp, Gold Rush, Wild Twist, Ludacrisp, and Rosalee), but don’t do more than half.

There are many excellent ways to make a pastry crust and to ensure that it doesn’t get soggy. My dad, who taught me to make apple pie as a kid, has now leveled up to a rough-puff pastry that he makes on an icy marble surface; if you’re not that sophisticated, many of my cookbooks recommend the all-butter pastry in a food processor method.

I don’t use either of those methods, preferring the old fashioned way of rubbing butter into the flour with my fingers. It might not yield many layers of puff or a totally perfect, even crust, but it’s a meditative experience. With my hands in the bowl, I feel connected to the pie and the people I’ll be feeding. I like that for five minutes, you can’t put your mind or your hands elsewhere. They are in the bowl with the butter and the flour. I like that there’s no set amount of water to get the buttery dough to cling together, because the moisture in the air, in the flour, and in the butter will change every time you make the crust. I like that you have to mix the water in little by little, getting a feel for exactly when the dough will press together and stay that way. It’s one of those cooking experiences that rewards patience, careful attention, and lots of practice.

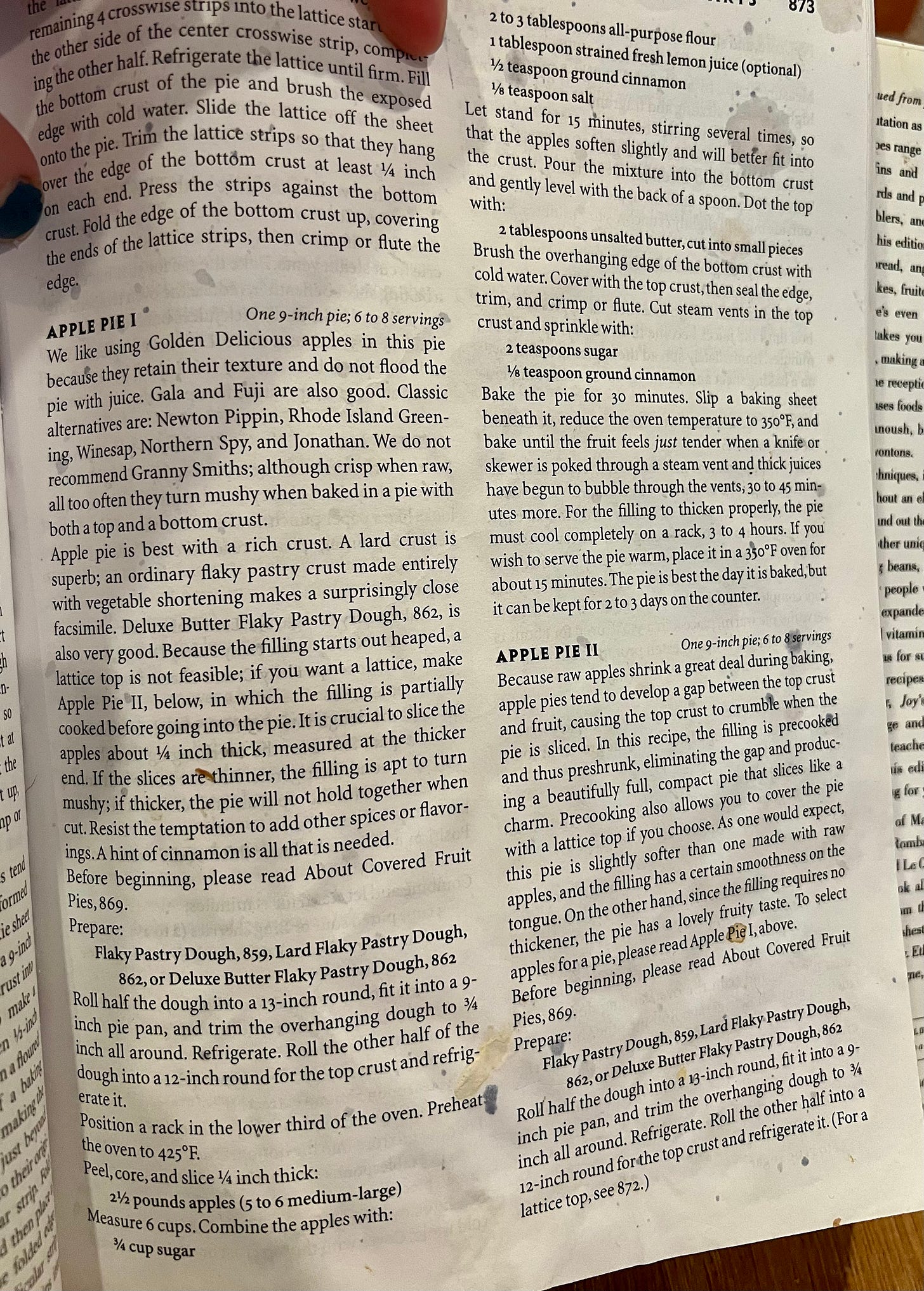

I’m not actually going to write out a recipe for an apple pie, because you could adapt almost any recipe based on what I’ve written. I do recommend that anyone who owns a copy of the Joy of Cooking should use that book for a deluxe all-butter pie crust and the original/”apple pie I” recipe: That’s what I refer to whenever I need refreshing.

One final cooking note: You should bake your apple pie for as long as you can bear it, and then you should let it cool completely. Plan ahead, make sure you bake it closer to two hours instead of one, and just watch it toward the end in case the crust might actually burn. You’ll end with a more texturally satisfying pie if you really prioritize that long baking and cooling time.

That’s all for this week, so I’m signing off with a collection of the totally wonderful things I’ve eaten in the last week…